Eddie and Tracy Foster in Montgomery City, Missouri, are on track to support the aspirations of the next generation that are tilling the soil and raising livestock. While some farming traditions have remained the same since the first Foster stepped onto the land, others have changed.

“My grandpa purchased the home 340 acres in 1944,” said Eddie Foster, who began following family farming traditions early in his life. “He farmed and had livestock, cattle and hogs. My dad started raising purebred Hampshire hogs in high school. He and my grandpa raised them on pasture in much the same way we still raise them today.”

“I bought my first Hampshire gilt with 175 dollars of birthday money when I was 5 years old and purchased my first 70 acres when I was 13,” notes Foster. Pastured hogs might be ‘old school,’ but raising hogs on pasture has worked for the Fosters since the 1950s and they have no plans to change things now.

Their 200 sow Hamp and crossbred farrow to finish operation begins in hotwire pens with an A-frame hut. The A-frames are moved closer to electricity for the winter, enabling the hogs to spend their entire lives on pasture. Rotated through pastures with summers spent in the brush, the sows are moved to fresh dirt when they are ready to pig. Once the pigs are weaned, they are grouped together on pasture and fed non-GMO feed in an antibiotic-free contract program.

“As the boys got older, we decided that either we needed to rent more ground or change the way we were doing things,” said Foster. Spending time on the road taking equipment to different rented fields was an unpleasant thought. “It made sense to us to generate more profit per acre rather than rent more ground. We transitioned to organic farming in 2007 and incorporated more livestock,” notes Foster.

Organic farming and adding to the livestock side of the operation met the need to generate more income and provided the best road forward for the Fosters.

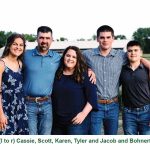

Transitioning to organic farming has enabled the operation to support several generations of the Foster family, including Eddie’s wife Tracy and their children—Kara (now married), Elden 24, Ruben 22 and Allen 20. Although Tracy wasn’t from a farming background, she quickly discovered life would revolve around farm commitments. “We moved the wedding and honeymoon up so I could be home when the sows would farrow,” Foster said. “We were married in August and home before September 1 when the sows were due.”

Farming organically has enabled five of the six Fosters to be fully employed on the farm, which Foster is certain wouldn’t be possible if they farmed traditionally. “Organic farming allows us to double our profit per acre, while decreasing our input costs and utilizing our older machinery.”

Feeling fortunate to work each day as a family, everyone plays a part in the operation. “Tracy does a bit of everything, and we all pitch in on the farming side. Elden and Allen are particularly interested in the livestock. Leaning more toward farming, Ruben is the machinery guy,” Foster said.

Livestock and Organic Farming Go Together Like Peas in a Pod

As a self-professed livestock guy that farms, Foster has a justifiable excuse to spend as much time as possible with the stock since their manure is an essential part of organic farming. “We couldn’t farm organically without livestock,” he says. Then the truth comes out, “I wouldn’t want to.”

Having the manure from the livestock isn’t the only benefit. The livestock utilize the crops when weeds and grasses sneak in and graze crop stubble.

The unpredictable weather and not having the luxury of using herbicides puts extra pressure on organic farming. “We always have a rotation plan, but it seldom works the way it’s planned.” Raising milo, oats, barley, corn, and soybeans gives Foster options to make adjustments throughout the year.

Chicken litter is the only manure purchased each year. In addition to hogs, the Fosters raise sheep and cattle, taking advantage of their ability to recycle crops and produce manure for the fields. “We have a colored commercial beef cow herd that are on pasture throughout the year,” adds Foster. Adding to the home-raised calves, the Fosters also background calves. “We purchase calves weighing around 400 lbs. and raise them to 550 or 650 lbs., depending on how much feed we have on hand.”

The calves are raised on pasture or in concrete barn lots depending on the weather, then are sent to Dodge City, Kansas, to be finished. Foster is partial to a mixed herd, saying, “As long as they raise a nice calf, they can be any color. Colored calves are cheaper to purchase. Once they are fat, they bring the same money as black-hided cattle.” Interestingly, in the extreme heat this summer in Kansas, the colored cattle did fine.

“Once the hides are off, it’s pretty hard to tell what color of cattle the steak came from,” says Foster.

Having a diversified operation, remaining flexible, and doing what works are the hallmarks of the Foster Farm. Staying with that trend, the boys have the reins of the Fosters’ hair sheep flock. The Katahdin and Dorper sheep excel at converting excess forage and crop residue into two lamb crops a year. Lambs are sold off the ewes at around 65 lbs. Lambing twice a year, early spring and again in late fall, works well to take advantage of the winter and spring higher market prices.

The plan is to expand the sheep flock, retain their ewe lambs and purchase additional replacements. “They are hoping to reach the point to capitalize on selling nice replacements, as well as sell all their lambs through video auctions,” Foster says.

“Our operation isn’t fancy; we don’t have the equipment payments that come with newer machinery either,” he notes. Foster jokes that the newest piece of machinery is an ‘06 self-propelled chopper that they purchased this summer. Most equipment is from the 60s, 70s, and 80s. “Our neighbors don’t need to go to the 50 years of progress show in Rantoul, Illinois. They can just look out the window.”

Knowing that success and longevity hinge on economics, Foster understands that inputs into the farm must be less than the money made from the various revenue streams. Organic farming and selling organic grain with the help of the National Farmers Organization has enabled the farm to continually expand and prosper.

“Mike Schulist is our NFO representative. He is a heck of a guy,” Foster says. “He makes sure we get all we have coming to us. I never have to worry, and that is a huge blessing. I have never worked with anyone who has our back like Mike.”

Encouraging their sons to explore their own dreams for the farm and giving them the freedom to learn from their mistakes and successes, Eddie and Tracy are excited to see what the future of organic farming and working with National Farmers Organizations holds in the years ahead.

The Fosters know that the hard work and dreams invested in their farm from previous generations and their family hold promise for the generations to follow. “As long as the next generation wants to farm, I am going to do all I can to ensure they have that opportunity,” Foster says.