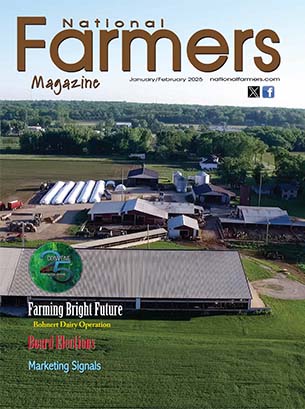

Pursley’s Persevere

By Denice Rackley

With our fingertips and technology, we reach across the planet, able to talk to and see people in every remote corner of the earth. We jump in our vehicles, and hit the road — hungry? We swing into a drive-through for a hot meal. Tired? We sleep safely in a hotel with a comfy bed and hot shower–and arrive at destinations hundreds of miles away in mere hours. Mountains, oceans, storms, and wild animals don’t slow us down, much less deter us in these modern times.

We tend to forget that not so long ago, traveling a couple hundred miles was a major undertaking, fraught with hardships, if you arrived at your destination at all.

During the 1800s, many set their sights on the west. Coming from the colonies, they slowly settled wild places like Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri. Navigating rivers – the Ohio, Mississippi, Missouri – hunting parties were often the first to explore new territories. Some of these men put down roots, carving a living out of the wilderness.

Just outside of St. Louis, the gateway to the west, the first Pursley, who accompanied a hunting party led by Daniel Boone, decided to call the rolling hills and fertile meadows near Robertsville home.

His decision has impacted the Pursley family ever since. Written deeds can be traced back to 1883, for this same land that now cradles three generations of Pursleys.

Stan Pursley can remember the Holstein cows dotting pastures owned by his great-grandfather. “The dairy was passed down to my father,” Stan recalled. Growing up, he vividly remembers being on the farm and the work required to keep everything running. “Of course, everyone helped with milking and chores.”

Long History Of Family Traditions And Service

“My dad was one of the founding members of the National Farmers Organization. His membership card is dated Nov. 1, 1958,” Stan said proudly. Like all farms of that era, they raised food for themselves and their stock, selling the excess, if indeed there was a bit extra.

“We transitioned to beef cattle about ten years after my dad took over the dairy,” he recalled. Feeling that serving the country and his community is of paramount importance, Stan began volunteering for the local firehouse after high school. Enjoying the work, he went to school to become a paramedic and firefighter. He worked in St. Louis County for 38 years, retiring in 2014. “The work supported my farming habit,” he said. Planting and harvesting fit nicely around long shifts and multiple days off.

Stan’s wife, Mary, worked in a laboratory at the local hospital. “She kept the place running while I was in school,” Stan commented. Not being from a farming family didn’t slow Mary down any.

She was a natural farmgirl; she just didn’t know it. “One of the first presents I gave her was a fishing pole. She was so excited. I took the fish off the hook for her, and I still do,” Stan recalled chuckling. “Mary is a better fisherman than I am. After all, she caught me.”

Mary also grows a fantastic garden and rocks homemade salsa. She enjoys crafts and is even the chief snake wrangler. “She gets mad at the black snakes for sneaking into the chicken house to eat eggs. She catches them and throws them into the haystack,” Stan said.

Their three boys enjoyed growing up on the farm, driving tractors and constantly exploring the outdoors. Dallas and his daughter, Jenna, live in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where he is the executive chef of a restaurant. “He always enjoyed food and cooking. He and his grandmother would cook together, which was fun to see,” Stan said. James is a certified public accountant. He keeps the books for the farm and lives nearby with his wife, Samie, and their two children, Samuel and Henry. Ben, the middle child, works as a conservation agent and is a farmer at heart.

“I used to think I wanted to do anything but farm, but now there is no place I’d rather be,” Ben said. Ben and his wife Sarah built a house on the farm and are raising their kids – Leo, ten, and Rosalie, seven – much like past generations did on those same acres. “I began driving tractors and helping in the fields when I was nine.” Leo is following in his dad’s footsteps; he began driving a tractor and raking hay this year. “So far, he enjoys it; we will see what the future holds,” Ben remarked.

The farming background works to Ben’s advantage. Most of Missouri is made of privately owned land, 93 percent actually. “Understanding where farmers are coming from when they call and complain the deer are eating their crop works to my advantage,” Ben noted.

“We double-crop corn and wheat, planting corn that is harvested in the fall, followed by wheat harvested in the spring, which is followed up by soybeans the next year. Hay not needed by the cattle is sold to neighbors, and we custom bale as well,” Ben said.

With the outskirts of St. Louis ever-expanding, any farmland that is sold is broken up into small acreages. “We have a good market selling to folks with a horse or two,” Stan said. The Pursleys maintain a herd of about 60 Angus cows that calve in the spring or fall but run as one group. “Calves are sold as feeders, 300 to 500 pounds,” Ben noted. A calf check twice a year is added to the custom hay business profits, and commodity checks from the crops maintain a cash influx for the farm since the outflow for seed, fertilizer, and repairs seems to occur all year long.

“My favorite activity on the farm is harvest,” Stan explained. “I enjoy shelling corn, the solitude, and being in nature.” Following the family tradition, the Pursleys market their grain with the assistance of National Famers and their representative, Lauren Neltner. Stan has been an active member of the organization. He enjoys the camaraderie and serving his fellow Missouri farms as the Missouri National Farmers Organization President.

Past and Future Tied To the Land

Producers across the country understand that farming is less about profits and more about a love for the land and family, with a good measure of faith needed. Committed to leaving the land to the next generation in better shape than they found it, Stan and Ben are grateful for the opportunity to raise their family on acres that have been handed down for nearly two centuries.

“When I was young, I viewed farming as something I had to do. Now I see it as something I get to do,” Ben said. Aware of the man hours, blood, sweat, tears, and sacrifice of generations past, Ben doesn’t feel he owns the land but rather that it has been entrusted to him.

“As beneficiaries, it would be an insult to every ancestor that has left their footprints on this land and had this very dirt on their hands not to do all we can do to pass it to our kids and make life here just a bit better for them.“ Ben explained. “The gift of the land is inextricably tied to our heritage.”